Recently I created a new Facebook group that I was hoping to focus on the more literary fantasy works of SFF. Mark Lawrence humorously named it as Literary Snobs of Fantasy.

If I’m not mistaken literary fantasy isn’t clearly defined anywhere however, which provided some uncertainty within the group when it came to book recommendations. I’m usually against labels and trying to shoehorn books into boxes but will endeavour to provide some guidance on what my views on the subject were when I created the group, hoping to spur and invite thoughts from others, rather than lay down rules set in stone.

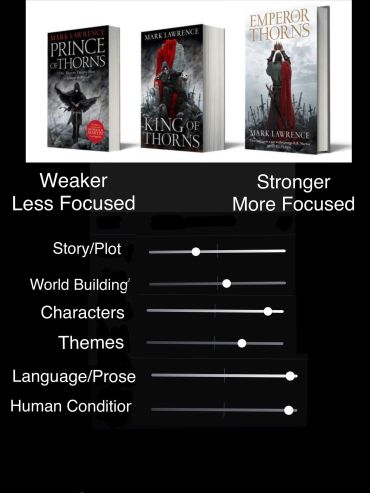

To illustrate my point, I created this little scale here. The underlying principle is that books which are not literary have a strong focus on the first element (plot) of the novel or the first two (plot and world building), while literary books concentrate on the last four.

To illustrate my point, I created this little scale here. The underlying principle is that books which are not literary have a strong focus on the first element (plot) of the novel or the first two (plot and world building), while literary books concentrate on the last four.

Just to be clear right at the start: A book being literary doesn’t mean it’s necessarily better, than a non-literary one. An amazing story told well, where the main focus is on telling that story and on not much else can easily be a great book and often a bestseller.

A book is always a mixture of these elements though. You can’t push the focus high on everything. If you push some of the lower categories too high, it will push back the plot for example. Talking a lot about how the characters feel or filling the pages with picturesque description or poetical musings will slow the story. Concentrating on various themes won’t leave enough space to develop intriguing storylines. The secret of any good book is often finding the right balance.

Considering another section of genre fiction, I’ve never particularly been a crime fiction fan. Yet, two of my all-time-favourite authors were writers of that genre. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who hasn’t just laid down some of the fundamental building blocks of modern crime fiction but introduced us to Sherlock Holmes’s wonderfully complex and intriguing character. This characterisation was very much part of why I fell in love with the stories in the first place.

My other favourite is Raymond Chandler. When I think about his books I feel that some of the lower buttons in my scale chart are pushed to the extreme right. Character. Prose. Human Condition. Yet Raymond Chandler adds literary content without turning the books into anything else than crime. He doesn’t “kill off” the genre, by overdoing the literary elements. Instead he makes it richer, better. And that’s exactly what literary content should achieve in genre fiction in my opinion. Not turning them into something unreadable by adding over-the-top flowery language, boring with focusing on descriptions and such too much. It should enrich our reading experience while still giving us a story of fantasy, crime, science-fiction or horror.

A few years ago I wrote a few thoughts on why the Broken Empire by Mark Lawrence felt literary to me. Below I will repeat what I said there as an example of fantasy being literary in my opinion as it’s relevant here:

In literary fiction characters generally come before the plot. While in fantasy literature we mostly get to know characters based on what they say and what they do, the dialogues and actions essentially becoming the plot itself, literary fiction also puts a heavy emphasis on what they think and how they feel, which often slows the plot. In The Broken Empire not only does the character come before plot but the plot in fact serves to illustrate/exercise the character.

In literary fiction characters generally come before the plot. While in fantasy literature we mostly get to know characters based on what they say and what they do, the dialogues and actions essentially becoming the plot itself, literary fiction also puts a heavy emphasis on what they think and how they feel, which often slows the plot. In The Broken Empire not only does the character come before plot but the plot in fact serves to illustrate/exercise the character.

The poetic, profound and masterfully crafted prose we find in the trilogy is also more of a ‘requirement’ of literary fiction, genre fiction readers being generally more interested in the story itself.

Finally, works of literary fiction are known to deliver a deeper reading experience, with themes depicting what it means to be human running under the surface of the plot. The characters undergo experiences which make the readers think and question certain aspects of life and with answers not provided they are expected to come to their own conclusions about them. In The Broken Empire one of these themes is how atrocities experienced in childhood may form the personality and how the person handles, grows around these hurts with time.

Children severely traumatized early in life do not easily bond with other people. They often cannot love or accept love, they can become children without conscience, who can hurt or even kill without remorse.

In The Broken Empire some of the questions we need to find our own answers for are whether such characters after all the violence and damage they caused on others might be still forgiven, whether they deserve any sympathy or at least, an understanding.

It’s also worth noting that while in The Red Queen’s War trilogy the plot gains a stronger position, the above elements still echo through it. The main character might be more shallow, rendering the prose less profound and philosophical, giving way to humour in turn, it is still very much character driven with much emphasis on the protagonist’s personality, – both as a consequence of childhood experiences and as something to be further refined on the anvil of the story.

Reblogged this on stewartstaffordblog and commented:

A rather interesting interpretation of fantasy. See what you think.

LikeLike

I would add one more category to the definition of what literary fiction is, which is that part of fiction which questions or experiments with the conventional purpose and form of the novel, the meaning of storytelling, and which deals with the relationship between the writer and the reader. The use of an unreliable narrator for example, multiple timelines or story within a story.

LikeLike

I would agree with your high opinion of Raymond Chandler, though as you say a writer outside the genre we’re considering. I would sing similar praises for Elmore Leonard, another crime writer, from a different direction – also not a fantasy example, but as another example of how a thinking writer can accurately reflect fhe world with a particular literary technique. One I’d like to see more of from fantasy writers.

His expertise was purely in crisp dialogue. The manner in which people speak in an everyday, even slang, fashion and written down so clearly in his crime novels.

The way we learn about and interact with everyone we meet is primarily through conversation, or even just short verbal exchanges. Leonard’s writing is usually almost pure dialogue. Most of what you learn about his characters is from what they say. Very little character description. Short descriptions of scenes. No long speeches. But crisp informative dialogue. His weakness was that the plots were not deep and in particular his heroic characters often had a common repetitive theme (e.g. bad boy/girl with a good heart).

That’s just another way a specific writer functions and it isn’t a universal message about how everyone should introduce characters. But I do hanker after fantasy literature with more realistic conversations. Not cursing in grandiose, classical fashions, real swearing when required. Describe the character via what they say rather than give an author’s description, via others thoughts, of their legendary cruelty/heroism, for example.

For me realistic, and not ‘literary’, conversation somewhat paradoxically forms a requirement of quality literature. Dickens did it well! Albeit without realistic swearing! Mark Lawrence is pretty good at the conversational side too….

LikeLike